For years, people blamed the global financial crisis on greed. Doesn’t this make you want to scream out, “what, were people not greedy in 2007 or 1997??” Greed utterly fails to explain the phenomenon. It merely serves to reinforce a previously-held belief. Far be it from us to challenge previously-held beliefs (OK, OK, we may engage in some sacred-ox-goring from time to time), but this is not a scientific approach to explaining observed events. To properly understand a crisis, you have to look for the root cause. And if the crisis did not occur previously, your theory needs to explain why not then, and why only now.

Suppose an old company, XYZ, goes out of business. “Times change,” people say, to explain an economic phenomenon. Or, perhaps slightly less imprecisely, “the market changed.” Sometimes they’ll get even closer to saying something. They say, “Company XYZ did not adapt to changes.”

These statements are copouts.

Times are always changing. Markets are always changing. If XYZ is an old company, then it obviously adapted to many big changes during its long life. So we need to get more specific. What change occurred to cause XYZ to go under? And to really understand it, why did the company not adapt to this change as it had to all previous changes?

For XYZ, we have in mind Radio Shack (yes we know, the latest iteration is not quite dead yet). Once a fixture in every mall and every town across America, it went into decline. What happened?

When we discuss the unhinged interest rate of an irredeemable currency, we usually talk about the falling cycle (i.e. when interest rates and prices fall). It makes sense, because rates have been falling since 1981. However, it can be interesting to compare to the prior rising cycle (1947-1981, when rates and prices were rising). Last week, we wrote about Keynes infamous quote of Lenin:

“There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency.”

Most people assume this refers to rising quantity of dollars, which they assume causes rising prices, which somehow destroys capitalism… Or something. It’s a bit vague. Lenin, in Keynes’s citation, goes on to say:

“The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

Keynes and Lenin are referring to something a bit more than just prices rising. They are not appealing to nostalgia, when gasoline was 26 cents a gallon, back when we had to walk both ways to school. Uphill. In the snow. Without shoes (which cost $2).

Last week, we talked about how a change in the unit of account gives the illusion of profitability. Radio Shack provides an interesting case to consider in light of how the times changed after 1981. No doubt there are other factors, but let’s look at inventory in light of the rising cycle that ended in 1981.

We believe every manufacturing and distribution company would have gotten into the game of selling bonds to accumulate inventory by the late 1970’s. Selling a bond is a win when the market price of the bond is sure to fall. Or to think of the mirror image, borrowing is a good deal if the rate is guaranteed to go up.

At the same time, inventory is guaranteed to go up in value. Buying inventory is also a win.

Radio Shack’s model was to stock retail stores with lots of low-velocity inventory. This was not just a reaction to the economic conditions of the rising cycle. It was the nature of stocking every size resistor, capacitor, and many other components. Hobbyists would come into the store because they knew it carried what they would need.

This need for lots of stock of slow-moving items fit the rising cycle perfectly. Who knows how long the average electronics component or roof-mounted CB antenna sat in the store before it was sold? Six months? In the days when prices were rising rapidly, this was an easy way to make profits.

When the cycle turned, most companies could begin liquidating inventory. At least once they realized what was happening and understood the strategy implications. Just in time inventory started to become the new buzzword.

However, for hapless Radio Shack, a large stock of inventory was not a tactical stance taken merely to exploit the rising cycle. It was inherent to its business model. What would you do, if you were CEO of Radio Shack in 1981, and knew all of this?

Radio Shack tried to evolve. It got into the computer business. It sold car phones, then cell phones, radio controlled cars, etc. These products, by nature, turn over much more rapidly.

They also compete for floor space, financing, and management resources with the company’s traditional product lines. Should the company have let go of its long-running products (and abandon its loyal customers) to try to compete with young PC or mobile phone companies? In new areas where Radio Shack had no particular advantage, and arguably a disadvantage in its corporate DNA?

Should it cling to an old strategy that fit the rising cycle hand-in-glove, once it rolled over to the falling cycle? Or should it try a compromise of both strategies, taxing the limited floor space of its retail stores?

Radio did not find the right answer.

We would like to leave you with two takeaways. One, the debasement of the dollar causes destruction of capital. It casts the illusion of profitability over a strategy which is mediocre at best—stocking retail stores full of slow-moving merchandise. This not only doesn’t work in today’s frenetic falling-rates environment, it wouldn’t work in the stable rate of a free market in money, i.e. the unadulterated gold standard.

Two, note how it encourages the growth of unsustainable models that will lead to bankruptcies when times change. This is a hard one for many investors to see. They think of themselves as smart enough to sell the stock. But the fact is someone owns it all the way down to zero. And some banks lend to these failing enterprises, and at the end of the day may realize pennies on the dollar. The Fed’s credit cycle destroys capital. Keynes and Lenin understood that it generally impoverishes everyone, though they knew that it “actually enriches some.” Even if you are one of the few who are enriched by trading this cycle, you should be aware that it’s destroying the civilization in which you live.

Upon closer examination, we can see that it’s not merely that some sort of times somehow happened to change in an unspecified way. We now understand that it’s an artificial and unnecessary cycle, created by the attempt to centrally plan credit. And the changes it causes are like a wrecking ball: first it smashes structures on one side of the street. Then when it swings to the other side, it does not repair the first damage. It wreaks more havoc.

The cycle will continue until it consumes all the capital that can be consumed, and we collapse, unable to produce food to sustain the population. Or until enough people demand an end to central planning of credit.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

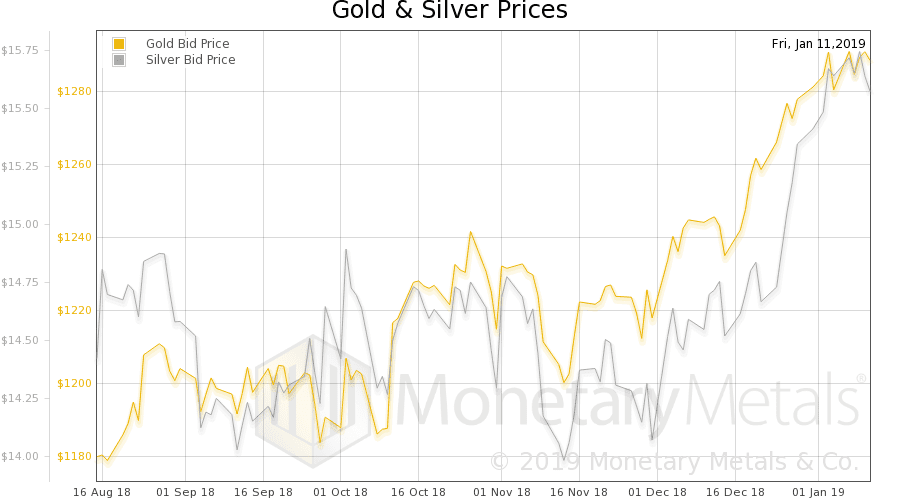

The price of gold went up two bucks, while that of silver fell ten pennies. Something’s odd about how the metals have traded. Back when the market thought that the Fed was tightening, the prices of gold and silver were rising. Silver is now about a buck higher than its Oct-Nov trading range.

But no sooner does Fed Chairman Powell say he is “listening” to the market—which is taken as a hint that he will stop tightening, if not ease a bit—than the prices of the metals stop rising.

Contracting money supply –> rising prices of gold and silver.

Expanding money supply –> softer prices.

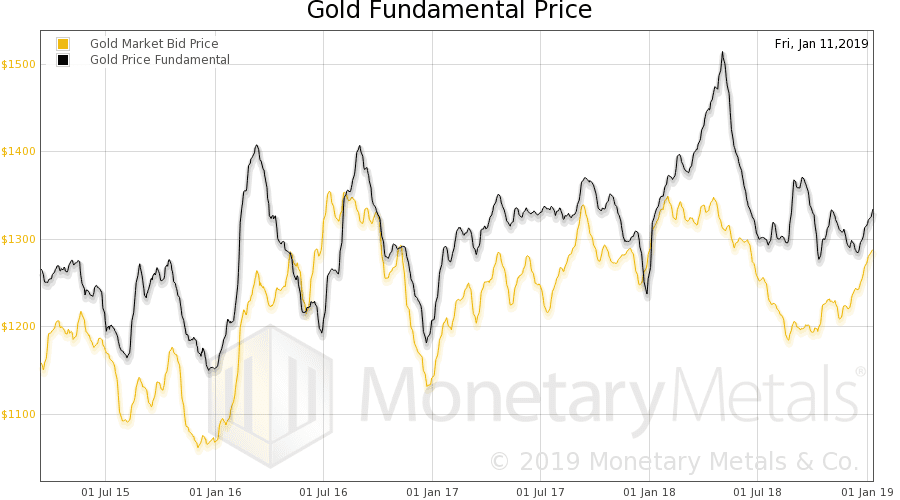

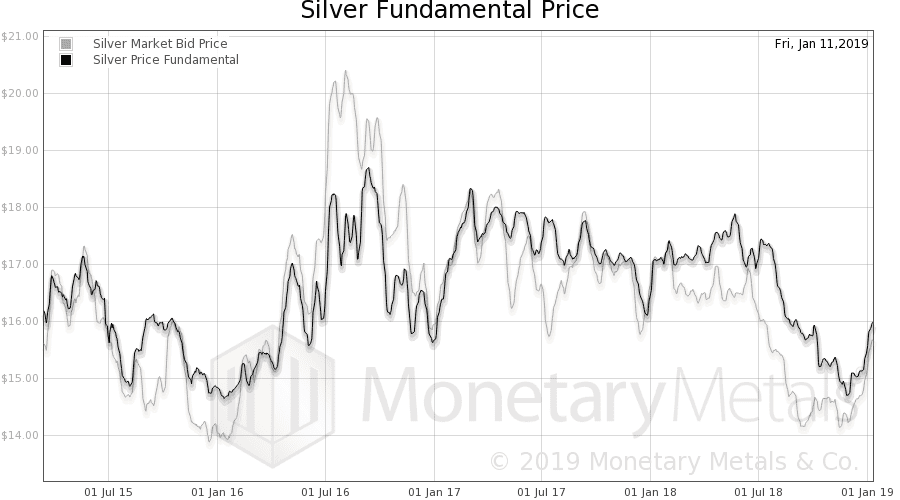

That said, the fundamental prices of both metals—a calculation we make every day—has been rising since Nov 26. So far, the listening and talking of Powell has not pushed the fundamentals down. Though it should be noted that the gold fundamental is just recovering to its range from 2017. And the silver fundamental is almost back to prior levels. We will look at graphs below.

But first, let’s look at that picture. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

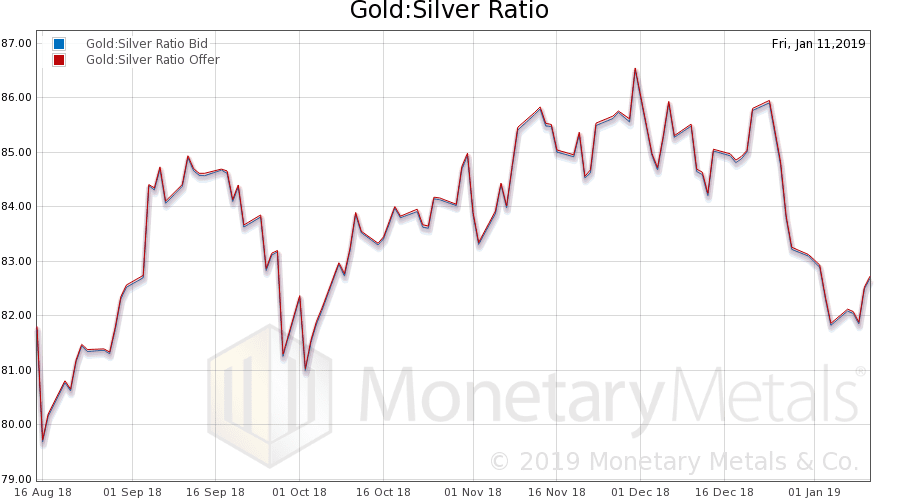

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It rose a bit this week.

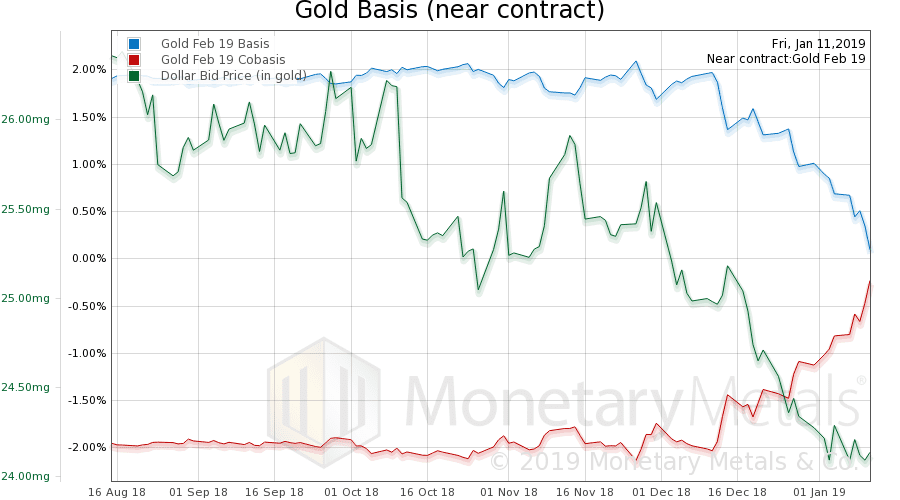

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

Keep in mind that this is the February contract, which is under selling pressure as it approaches expiry. Though the gold continuous basis rose a bit too.

Here is the graph of the gold fundamental price for 1,400 days.

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price rose $23 to $1,344.

Now let’s look at silver.

As the price of silver fell a bit, the cobasis (scarcity) rose a bit.

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 9 cents, to $16.00.

Here is a graph of the silver fundamental.

© 2019 Monetary Metals